“I’m not coming back.”

Don Blanton says these were his father Charles’s last words to him, spoken as the man suffered a heart attack and waited for an ambulance.

Just those words. No hug or advice.

Blanton still misses hugs that never came from his father. But over time, he discovered and refined a lesson from that moment half a century ago: make your life matter.

His father was 52 when he died. When Blanton reached that same age, he quit his managerial job at an aerospace factory in Connecticut to pursue a full-time career as an artist and teacher, putting a childhood dream on hold.

“He taught me by what he didn’t do,” Blanton says of his father.

Today, at the age of 82, Blanton has more than twenty painting and sculpture projects underway. He traveled to Boston last week to attend an exhibition of his work. On Wednesday, the Republican published the Juneteenth poster that Blanton created in 2022 for the Springfield Symphony Orchestra concert.

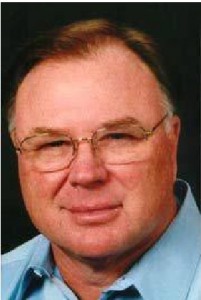

Springfield artist Don Blanton in the studio at his home. (Don Treeger / The Republican) 6/6/2024

He is taking steps to resume the education and mentorship that helped inspire artistic expression in hundreds of Pioneer Valley residents of all ages as he completes a course of chemotherapy after undergoing surgery for stomach cancer.

This month I visited Blanton’s studio in the city’s Sixteen Acres neighborhood for two extended lectures on his life in art. These conversations are presented here in edited and abridged form.

Q: When have you felt like you could leave a job not wanting to follow your heart?

A: I think I’ve always felt that way. It’s just that society makes us think that we have to go somewhere else and depend on someone else.

I thought, when I was working in Connecticut, I couldn’t do this anymore. I’m not going to croak tonight and say I should have become an artist. So I just said, “That’s it. I do not mind. I have to sabotage this job. I will do everything I can not to come back.” And I meant it.

Q: Was there a moment when you realized that working as an artist could provide you with a livelihood?

A: I sold my first painting when I was probably 12 or 13, as a black young man in Richmond, Indiana – and I was so lucky, and I’ll tell you why.

My brother, Paul, and I would often go to Main Street and ask merchants if we could put out our little paintings and sell them for $2 or $3 each. One day a man in a suit and tie pointed to a painting of mine I called “Silent Storm,” with hanging leaves, and said, “Well, how much is that?” I looked at him and said, “$40.” My father made about $40 a week as a janitor. He reaches into his pocket and pulls out $40.

My brother said, ‘Tell the truth.’ I told the guy, “Okay, it’s $4.” And the guy says to me, “Oh no, that work is worth more than $4.” He says, “I’ll take it.” I said to myself, “Man, I gotta keep doing this.” All I could think about was, “My father worked more than forty hours and didn’t make that much money. And I made that.”

Q: What did it take to reach the milestone of full-time artist? What did it mean to you?

A: That factory job literally made me sick. Sick of babysitting adults. I find it difficult to deal with such people. Because negativity brings you down.

And I said, “It’s just not me.” I don’t care what they pay me. You have to understand that I probably started working at the age of 11. And never stopped. I mowed grass. I shined shoes. I shoveled snow. I’ve done a lot. And I saved a lot of my money.

I said, let’s think about that. I am 52 years old and was 11 years old when I started working. I figured if I can’t sit down for a month and figure out what my next step is, then there’s something wrong here.

Many people love art. Many people absolutely love it. My father always said, ‘Oh yeah, do you think you’re going to be an artist? You’ll starve.” I’ve heard that since I was little. But guess what? I didn’t believe it.

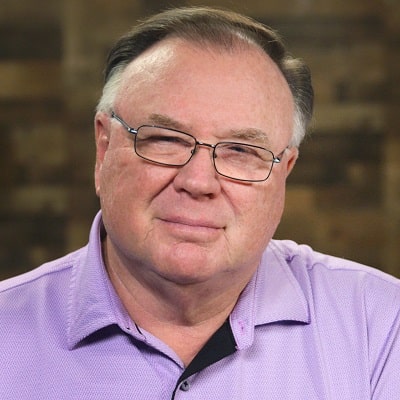

Springfield artist Don Blanton’s hand is working on a sculpture in the studio at his home. (Don Treeger / The Republican) 6/6/2024

Q: What did it mean when you finally got through that passage?

A: Oh, it was almost like a weight was lifted off my shoulders. I started to feel better physically and mentally – much better. And I knew I was doing the right thing.

Q: You told me that you got in trouble in elementary school in Indiana for refusing to read a racist children’s book, “Little Black Sambo,” which resulted in an unusual encounter with a white teacher. What did you get from that?

A: The teacher says to me, Donald, I want you to stay after school. And I did. She says to me, after everyone had left, “Why don’t you just read it and get it over with?” And I told her, “I’m not going to read that.” She knew that I was also punished at home. So the teacher says to me, “Are you ashamed of being black?” And I told her no. Then she made a mistake by saying to me, “You have heroes, Donald, you have Joe Lewis and Jackie Robinson and Jesse Owens.”

Do you know what I told her? “Then why can’t we read about it?”

She says, “Donald, you were clearly born at the wrong time, you’re so far ahead.” She said that one day these types of books will no longer be allowed. And this big woman pulled me to her and hugged me and said, “Donald, I’m so sorry.”

Q: You said that your early painting, “Silent Storm,” was a landscape. What made you want to capture the world in visual art?

A: The way I look at everything – whether it’s politics, sociology, psychology – it’s all human behavior. Art, and culture and painting, go back so far for me. It reflects society and culture. Human behavior is connected to art. That’s it really. It’s what’s inside me.

I tell people, ‘I haven’t found art. Art found me.” It came to me. I can’t turn it off. I have – and I am not exaggerating – probably twenty different sculptures and paintings in production.

Q: How has the Juneteenth holiday – which celebrates the word of emancipation reaching enslaved people in Texas – inspired you as an artist? As an artist, did you feel an acceleration in possibilities?

A: Without a doubt.

Juneteenth poster by Springfield artist Don Blanton. (Photo by Chris Marion)

Q: Some of the figures in your Juneteenth work are shown in profile. That suggests to me a sense of mass, an almost infinite number of people represented. How did you make choices about where to go with this work?

A: More than anything, the colors, the strong colors. The colors are festive. You want to celebrate what it is. What everyone has experienced. Everything they saw. All sacrifices.

Question: Your representation of figures suggests masks. There is a serenity and a peacefulness about the expressions. What is the meaning of masking in this piece?

A: It’s about masking your feelings. The teacher I initially mentioned tried to make me feel ashamed of my color and myself. At a point where you put on a mask, you are protected.

At that same Fairview Elementary School, I got in trouble with a teacher who said, “Put him in the back.” He’s not paying attention.”

Do you know what I was doing? Drawing African faces on my hand, but I didn’t want anyone to see that. I put my hand down. I had to be seven or eight. But for some reason I had come to know Picasso. And he was influenced by African art.

Question: What does the word emancipation mean to you? Do you think there is a sense of emancipation in the work you make?

Answer: It must be so. I’ve read so much about the Irish and about the Italians who came here. Africans were the only ones who came in chains and had to be emancipated. I think that’s the driving force for a lot of it.

Emancipation – it makes me work harder. It makes me do better financially. Pulling your own strings is important.

Q: What determines the way your art comes out of you?

A: Personally, I like art that I’ve never seen before. I’ve seen a lot of landscapes. I’m trying to create something you’ve never seen before. We grew up thinking that we want our work to be different. That it is the only one in this entire world.

Q: What kind of artistic legacy do you think you are leaving behind?

A: Be respectful, treat people a certain way. Whatever you do, keep doing your best. At least I left something in here. I came here for a reason. I really mean that. I was put on earth for a reason, and I am going to fulfill it. I’m going to do my best.

I say the journey is more important than the destination.

This work by Springfield artist Don Blanton hangs in the studio at his home. (Don Treeger / The Republican) 6/6/2024

Q: When you talk about the “journey,” do you mean that your work is the journey?

A: Yes, and what happens along the way. Like the woman in Springfield who one day, many years ago, organized a ticket sale and gave me free sculpting tools. That’s part of the journey. I would like to find her and speak to her again – to thank her.

Q: Do you feel like people want you to be a black artist?

A: Yes, there are people who would say that. I feel like, don’t just call me on Black History Month. I always got angry when I got a call like that. I will participate in it. But I want to participate in everything else. I didn’t choose to be black. I have chosen to continue what I do artistically.

Q: Do you think you bring elements to your work that are unique to your experience as a Black man?

A: Absolutely. Absolute.

Q: How do the most effective art teachers help their students?

A: By working with them with sincerity. Knowing that they know you are there to help them excel. And use yourself as an example in how you treat them. With a sincere heart I speak the truth. It’s like tough love.

Q: Is it fair to say that your heart lies in both creating art and helping other people find their path to creativity?

A: I’m an old man trying to get to heaven. One thing about art, and Don Blanton, is that my art will live on through other people.