:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/1924Olympics-56a48e1d3df78cf77282f13e.jpg)

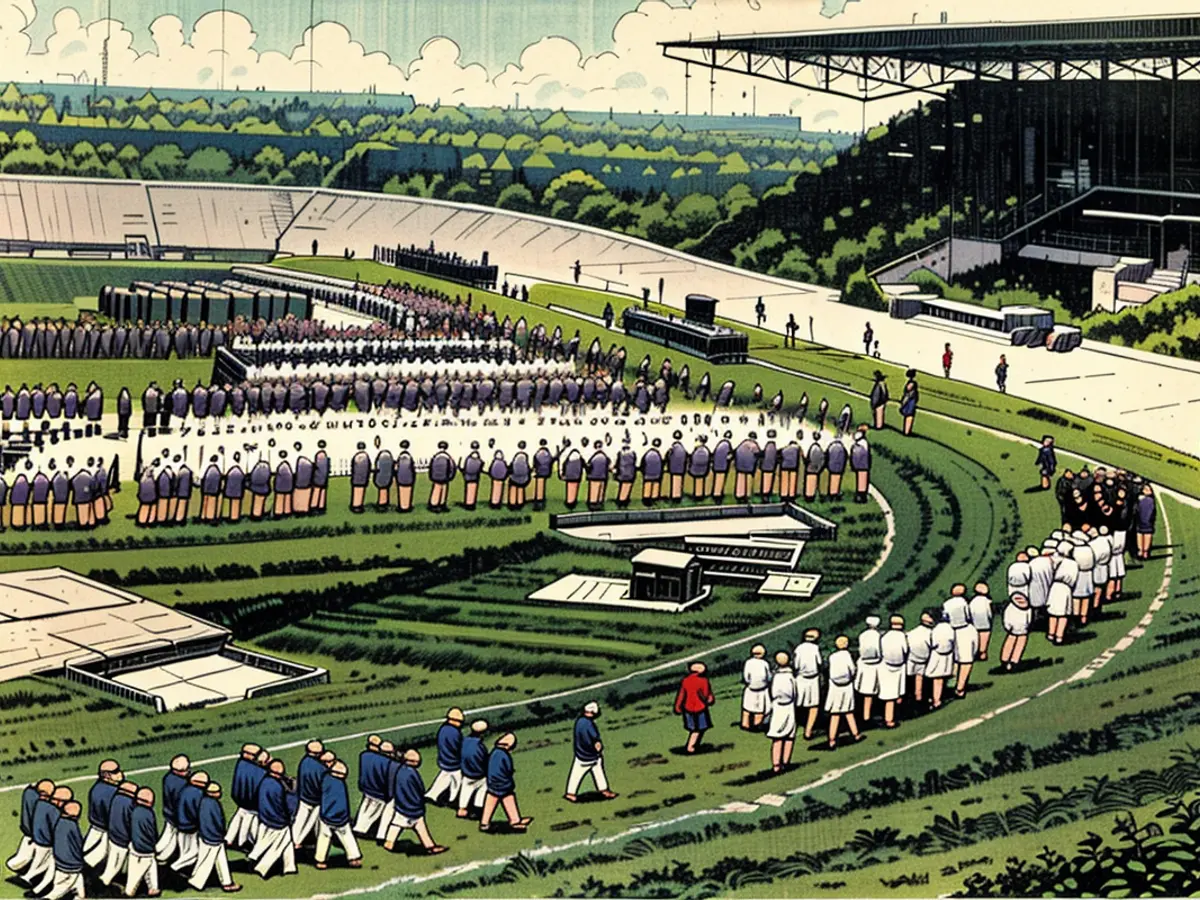

‘Chariots of Fire’ immortalized the 1924 Paris Olympics. Decades after its release, the film has ‘taken on a life of its own’

Thus begins the Oscar-winning 1981 film “Chariots of Fire,” which introduces a group of British athletes as they train for the Olympics.

The runners – their T-shirts and shorts stained by sand and sea – splash through shallow water toward the Scottish coastal town of St. Andrews, which slowly appears as a series of spires and rooftops on the horizon.

The scene is embedded in film history, memorably capturing the quiet beauty of walking across a deserted beach. The simple joy of running becomes a central theme of the film, even as the athletes’ faces are now a mix of hardship, happiness and determination.

“The beautiful thing about track and field, unlike almost any other sport, is the lack of complexity,” says David Puttnam, the producer of “Chariots of Fire.” CNN Sports. “You throw something, you jump over something or you run. It’s actually a quintessence of human effort.”

Perhaps it is for this reason that the film remains so popular and recognizable more than forty years after its release.

Based on the lives and gold medal-winning exploits of sprinters Eric Liddell and Harold Abrahams prior to the 1924 Olympic Games in Paris, “Chariots of Fire” won four Oscars – including Best Picture. It is arranged one of the greatest British films of all time, and was a favorite of former and current US Presidents Ronald Reagan and Joe Biden.

With the Olympic Games returning to Paris this year, public screenings have been held in several countries, offering a timely reminder of how “Chariots of Fire” still carries a charming appeal and an uplifting – even life-saving – message.

“After the film came out, I must have gotten – and this is no exaggeration – at least half a dozen letters from people saying that the film had made them decide not to commit suicide, that life was worth living,” Puttnam says.

“The film has a way of really, really speaking to people… something much more than we imagined or probably put into it. It has a life of its own.”

“Chariots of Fire” highlights the athletic careers of Liddell and Abrahams – both talented sprinters – in the years leading up to the 1924 Olympic Games.

Liddell is a friendly figure with strong religious convictions, a missionary in his native Scotland who withdraws from the 100 metres at the Olympics because the heats are held on a Sunday. Instead, he runs the 400 metres – and wins – despite his limited experience running the longer distance.

The moment is the emotional high point of “Chariots of Fire,” as Liddell, played by Ian Charleson, describes how his running has become intertwined with religion: “God made me for a purpose, but he also made me fast. And when I run, I feel his joy.”

Liddell was a Scottish rugby international before becoming an Olympic champion. He has been praised for his selflessness and his sporting achievements. He was born in China and returned there to serve as a missionary teacher after the Olympics. He remained largely in Asia until his death in a Japanese internment camp 20 years later.

“I had a lot of space in my heart for him,” former Scottish sprinter Allan Wells, who won gold in the 100m at the 1980 Moscow Olympics, told CNN Sport. “He’s a very special person and he really gave of himself. It’s a huge legacy and we shouldn’t forget him.”

Wells recalls being asked after his race in Moscow if he would dedicate the victory to Abrahams, Liddell’s counterpart in “Chariots of Fire” and until then the last British man to win gold in the 100 metres.

“It was a case of just throwing it down my throat,” he says. “I thought for two or three seconds and said, ‘No, if I’ve done it for anyone, I’ve done it for Eric Liddell.’ Luckily there were three Scottish reporters sitting at the back of the room and they all gave me the thumbs up.

“I think there is a connection, but he (Liddell) was much more special than me… Maybe 20, 30, 40 years after I’m gone, they’ll remember Eric Liddell before they remember Allan Wells.”

Liddell’s philanthropic legacy lives on The Eric Liddell Communitya dementia care charity in Edinburgh, with a focus on older people, loneliness and isolation.

This year the organization started with The Eric Liddell 100 Initiativeintended to raise awareness of Liddell’s life among younger generations and to recognise his heroic deeds following the Japanese invasion of China in 1931.

“When he was in China, he apparently told people to pray for the Japanese – and they were the people who were holding them in the internment camp,” Sue Caton, Liddell’s cousin and a patron of the Eric Liddell Community, told CNN Sport.

“He cared about everybody. He would never have fired anybody, no matter who they were or what they had done, because he thought that was what we had to do.”

John MacMillan, chairman of the Eric Liddell Community, agrees, even noting that some people in China have welcomed Liddell as their first unofficial Olympic gold medalist.

“He was clearly a determined person, he was a dedicated person, and he clearly put the needs of others before his own needs,” MacMillan says. “He’s remembered as a sort of Robin Hood figure.”

Abrahams provides a striking counterbalance to Liddell in “Chariots of Fire”, his conviction and strength of personality no less powerful.

The film also presents Abraham’s faith as a motivating factor in his running career. Anti-Semitism forms the backdrop of his time as a Cambridge student, and his athletic prowess is described as “a weapon … against Jewishness.”

“I placed so much importance on my athletics as a means of showing that I was not inferior,” Abrahams, who died three years before the film’s release, once said. said in an interview with the BBC in the 1960s.

“It played a huge part in my life. I think you overstate it – there was a certain amount of anti-Semitism when I was a young man, and there is a certain amount now. But I was so determined to demonstrate my superiority that I put everything on athletics.”

For Abrahams, running was an all-consuming activity, so much so that he often became anxious and obsessive about his performances – a detail noted by actor Ben Kruis in “Chariots of Fire.” He tells coach Sam Mussabini on the eve of the Olympic 100-meter final, “I’ve known the fear of losing, and now I’m almost too afraid to win.”

Abrahams’ nervous, uneasy relationship with the racing world was almost self-destructive.

“Harold Abrahams was an extremely neurotic man, and to say he was very tense is almost an understatement,” said author Mark Ryan, whose book “The chariots return” tells CNN Sport about the lives and influence of Liddell and Abrahams.

“He went through absolute hell before races, almost complete nervous breakdowns. The fear was the anticipation, that people had come there to see him win, but that they would also laugh when he lost.”

However, Liddell’s nerves, which he had early in his career, disappeared over time.

“He got over that pretty quickly when he realized he could connect his running with his Christianity in his head,” Ryan adds, “and then all the pressure went away. He still hated to lose, but if it was God’s will for him not to win, he didn’t win. It was all for the glory of God, and what’s going to happen, is going to happen. That was a great mindset to take with him into any race, I think.”

Abrahams badly injured his leg in the long jump the year after the Paris Olympics, forcing him to retire from athletics. He became an influential journalist, broadcaster and athletics administrator, and remains one of only three British men to win the Olympic 100m title.

“Chariots of Fire” has ensured that Liddell and Abrahams’ achievements are not lost in time, but the film is not an accurate representation of their lives.

For example, Liddell decided not to run the 100m for the Games, unlike the 11th-hour decision presented in the film. His bronze medal in the 200m is also skipped, while the athletes’ training in the opening scene took place not in St Andrews but in Broadstairs, a town in the south of England.

Puttnam, who has acknowledged the film’s artistic freedom, says he never anticipated its success, not least because of budgetary constraints – he had $6 million at his disposal – and the many logistical hurdles.

When it came to the Oscars, he didn’t care and never expected to walk up on stage to accept the award for Best Picture.

“I remember getting up, knees wobbly, and going down (to the podium),” he says. “My hair wasn’t cut yet — this is a shot of me trying to get my hair in a certain order, because if I thought I was going to win, I probably would have cut my hair.”

Filming “Chariots of Fire,” like preparing for the Olympics, was a laborious process. The actors trained for six weeks under the guidance of veteran Olympic coach Tom McNab to get in shape for the running scenes, while Nigel Havers, who plays Lord Andrew Lindsey, fell and broke his wrist while learning to run hurdles.

“If you ever meet him, his wrist is on the wonk,” Puttnam says. “He knew if he went to a doctor, we’d have to recast the movie, so he didn’t tell anyone. … I’ve always been in awe of his courage.”

Courage, fittingly enough, is at the heart of Chariots of Fire – whether it’s Liddell’s decision not to bow to the pressures of a Sunday run or Abrahams’s bracing for the 100m final race. And while the film is about dedication, commitment and an unbridled love of running, it’s also, somewhat cynically, about winning.

“Would I have done it if Liddell had won a silver medal? The answer is no, I wouldn’t,” Puttnam muses. “That wouldn’t be the point.”

History is written by the victors, or so the saying goes. And that seems like a fitting message for one of the most iconic sports films ever made.

The producer of the Oscar-winning film “Chariots of Fire”, David Puttnam, emphasizes the simplicity and directness of athletics, stating that “it is really the essence of human endeavor.” ( contains (‘sport’) )

Former Scottish sprinter Allan Wells reflects on the impact of the film “Chariots of Fire” and says that after winning the gold medal in the 100 metres at the 1980 Moscow Olympics, he chose to dedicate his victory to Eric Liddell, a central figure in the film. ( contains (‘sports’) )